Jonathan Luxmoore and Christine Ellis

From anti-Vietnam war ballads to miner’s strike songs, folk artists have long voiced countercultural anger. With so much ammunition today, could folk music be about to wake from its recent docility?

Willie Nelson opening the Fourth of July Picnic festival in 1974. Photograph: Everett/Rex Shutterstock

Last November, the folk singers Nancy Kerr, Martyn Joseph, Sam Carter and Maz O’Connor went to Westminster to perform for MPs. Nothing so remarkable about that, perhaps, but what they were singing about might have made several of their audience a little uncomfortable. The musicians were there to launch Sweet Liberties, a project marking 800 years of British democracy as seen through episodes from the Levellers and Tolpuddle Martyrs to the modern-day Race Relations and Human Rights Acts.

In a year that marked the 800th anniversary of the sealing of Magna Carta and 750 years since the Simon de Montfort parliament, the four celebrated the pursuit of democracy and sung songs new and old, written about the rights and liberties that people have fought to achieve and protect over the centuries. “The topics in our songs all deserve to be celebrated – but we’d also like to highlight some uncomfortable truths which matter to vulnerable people today,” says Kerr. “Folk music reflects the creativity of working people, who often used it as a political voice. This kind of project could link present concerns with previous radical struggles and help us find a new collective voice.”

Kerr’s mother, Sandra, was a “folk apprentice” to Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, whose Critics Group met in London’s Union Tavern in the 1960s and 70s to promote political change through music. Kerr has long since established her own profile (she won 2015’s BBC folk singer of the year award) and believes current issues, from fracking to climate change to welfare cuts, offer rich material. She is disappointed that what she terms the “artistic left” seems to have backed off from the politically focused music that MacColl and co once sung. Where have all the protest songs gone?

The reasons behind the silence range from the generational to the cultural and economic. While politics remains a prominent subject in the arts as a whole – with standup and fringe theatre routinely used for agitprop – some claim that changing social habits have eroded music’s political significance.

“Protest songs are no longer seen as an effective form of communication,” says Malcolm Taylor, a folk music expert and former librarian at the English Folk Dance and Song Society. “There’s so much ammunition for them, and if you wrote one that happened to catch on, you could potentially reach millions. But whereas Billy Bragg and his generation would have strapped on their guitars and headed for a street corner to make their point, today’s discontents prefer Facebook and other social media.”

Bragg’s generation in the 1970s and 1980s could also draw inspiration from the US, where legendary protest artists such as Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Alan Lomax had ended up on Senator Joe McCarthy’s blacklist, and later arrivals such as Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs and Joan Baez lent musical backing to the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements. Music was, for a time, a powerful countercultural force.

In the UK, too, folk music was long a tool of political protest, influencing writers from Chaucer and Shakespeare to Dickens and Hardy. Songs helped shape popular moods: Richard Thompson’s Blackleg Miner highlighted the plight of colliery workers, while Song of the Lower Classes by the chartist poet MP Ernest Jones drew on rousing works such asShelley’s Mask of Anarchy.

In the late 19th century, thanks to pioneering collections byCecil Sharp, Lucy Broadwood and others, folk music gained respectability. Many believe it lost its bite in the process. But in the 1950s, MacColl roundly rejected the genteel, sanitised legacy of Sharp and his co-collectors and set about turning folk music into a vehicle for radical change. MacColl’s own revival of Travellers’ Songs highlighted the plight of Roma communities, while compositions of his own, such asFreeborn Man and Song of the Road, also fed into a political agenda. MeanwhileAL Lloyd – who was barred from the BBC because of his Marxist sympathies – identified an anti-authoritarian tradition in English folk that stretched back to the Peasants’ Revolt. His seminal Penguin Book of English Folk Songs from 1958, compiled with Ralph Vaughan Williams, was intended to dismiss “the false supposition that folk songs are always ‘quite nice’” and return folk to its earthy roots.

It was a mission taken up at the time by Topic Records, a 1939 offshoot of the Workers Music Association, the world’s oldest independent label. “From Sharp’s collections, it’s clear the ballads and broadsides of old present an alternative view of key phases in history, such as the Industrial Revolution and Napoleonic wars. As such, some leftwing historians have seen them as significant testimonies,” Taylor says. “But MacColl and Lloyd also bowdlerised them and used them for their own political ends, much to the dismay of other folk performers who didn’t share their radical views”.

The UK’s folk protest tradition lived on in the songs of Bragg, and veterans such as Dick Gaughan and Steve Knightley. But since then, few younger performers have seemed interested in addressing political issues on stage. And while the protest mantle was assumed by punk and new wave bands raging against the Thatcher government, their own counterculture has long since been co-opted by polite society and exploited by the UK’s booming music industry.

Much the same appears to have happened with mainstream hip-hop, which once existed as an expression of protest but has since been largely depoliticised by the effects of fashion and business sponsorship.

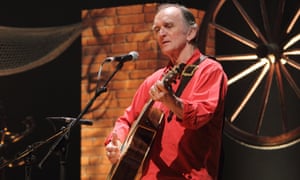

Taylor believes all forms of protest music have eventually been “appropriated by the establishment to make money”. The veteran folk artist Martin Carthy agrees. “There are still some good and effective protest singers and songwriters around, but it’s not like it was in the 50s and 60s”, he says. “The promoters have long since cottoned on to the commercial potential of protest music; you’d have to be very determined and energetic to make yourself authentic and visible without them.”

The decline of radical politics in the 1990s alongside the rise of New Labour undoubtedly contributed to folk music’s new docility, the genre offering little in the years when the Occupy movement and anti-Iraq war demonstrators have taken to the streets in protest.

But things might be changing. Jeremy Corbyn’s rise to political prominence has spurred new radical thinking, which could well gain a platform in music. Carthy recently rewrote a folk classic, Rigs of the Time, with references to “rich corporate farmers” and the European Union’s agricultural policy. His daughter Eliza has also worked political messages into songs of her own, such as You Know Me, about the plight of refugees, and Fisherman, about the Occupy movement. Not that protest songs are the exclusive domain of the left: the folk tradition has encompassed Jacobite rants and classics such as the royalist civil war song,Dominion of the Sword, while contemporary singers such as Morrissey and Gary Numan have pitched in for the political right.

“While I’d prefer protest songs to come from the left, I accept that every political option can produce them since folk is music of the people”, Carthy says. “We’re clearly seeing a widening out of political debate, so I don’t see why this tradition couldn’t revive. If we’ve a duty to pass folk music on, we should also bring it up to date and make it relevant to our times,” he says.

Kerr hopes the Sweet Liberties project will go some way to providing “a soundtrack for current anxieties” at a time when young people are showing a new readiness to engage with and get involved in politics. “No one’s going to write a song today which starts a revolution, but I like the idea of a musical movement where different voices can bring their ideological concerns to bear,” the singer-songwriter says.

“We may not see the like of We Shall Overcome [the seminal civil rights anthem] again. But we can still smuggle some subversive, powerful, galvanising ideas through in music. And this may well be a time when people are wanting to hear them again.”

- Jonathan Luxmoore is a freelance writer. Christine Ellis is an Oxford University librarian. They are both amateur folk musicians.